Global Marketing Monitor: Weekly Market Trends (September 12, 2021)

- POV’s

- September 11, 2021

- Brian Wieser

WHAT YOU’LL READ ABOUT THIS WEEK:

We review the biggest news of the past week (a court ruling which will force Apple to open up its payments systems to developers) and one of the biggest news items of the past year (significant changes in the Chinese government’s policies towards technology companies, which include many of the world’s largest sellers of advertising), with an eye on the implications for marketers. In between, we review new data on DTC business models and current trends related to the global consumer packaged goods industry in an attempt to better assess the broader health of those important sectors for the advertising economy.

Apple App Store Ruling: Read-Through For Marketers

One of the past week’s biggest news items relevant to media industries relates to a US court ruling on Friday relates to the Epic Games – Apple lawsuit. As a consequence of this ruling, Apple will effectively no longer be allowed to prohibit developers from using third-party payment mechanisms, which in turn should allow companies who sell digital products, such as game developers and other media companies to either establish their own payment systems or use payment systems from other companies which would charge less than Apple’s 30% commission rate.

On its face, the news certainly has favorable financial consequences for companies that sell virtual products today. Perhaps more interestingly, we can contemplate a world where manufacturers of physical goods choose to invest more heavily in virtual products or digital services knowing that they won’t have to share as much as they would have to presently. Consumer experiences will also likely change if developers who today route consumers to websites to make payments can now do so within their apps instead. Overall, a lower transaction cost environment for digital products within apps should lead to more development of app-based activities for all kinds of marketers.

DTC Companies: Securities Filings From Allbirds and Warby Parker Provide Extra Insights Into Important Business Trend

One of the better illustrations of “creative destruction” in the economy has been the emergence of direct-to-consumer brands over the past decade. While the specific definition of a DTC brand can be somewhat subjective, we think of them as including a wide array of companies primarily in highly consumer-focused categories such as apparel, food and packaged goods. Historically, they featured digital storefronts along with some elements of customer service and fulfillment, aided by advertising strategies that relied on high degrees of targeting on social media platforms. While many of these companies sold goods on an individual product basis, they also commonly featured subscription-based business models. Perhaps most notably, many of them outsourced the bulk of their operations, including manufacturing. Putting all of these features together, many companies quickly established themselves as important challengers in their categories or new sectors adjacent to older ones.

The perceived successes of these companies – or at least the high-profile, high-value venture capital fundraisings which were completed, paired with the occasional eyebrow-raising sale to a strategic buyer at a time when global packaged goods companies were experiencing low growth – led to a significant amount of attention on the space. However, as early growth-hacking strategies reached their limits, many DTC brand owners adapted and began to embrace traditional strategies, such as selling products through traditional retail environments, whether via owned stores or through third parties.

The news-worthy update to this sector relates to recent IPO filings by two of the best-known entities within the DTC space, Allbirds and Warby Parker. Last month both companies filed documents with the SEC as part of the process of becoming public companies. They followed on IPOs earlier this year for Honest Company and BarkBox, as well as prior public offerings from BlueApron, Casper, Hello Fresh, Peloton and Purple, among others. For students of economic change, the broader number of companies with public data is helpful as we have increasingly meaningful data through which we can better understand DTC business models.

Among the most interesting takeaways from our read on filings from these companies:

- Advertising expenses as a percentage of revenue remains remarkably, if unsurprisingly high, with figures ranging from 10-30% on an annual basis. These percentages appear to be declining in general at the individual company level, although all companies making disclosures did show growth in absolute spending during 2020 over 2019.

- DTC companies are relatively small, despite the positive size bias associated with companies that tend to become publicly listed. Among this group of companies, Hello Fresh and Peloton generate revenues that are measured in the billions. However, all of the others (and presumably almost every other company we might describe as a DTC business) generates revenues at a smaller scale. Most of the companies listed here generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually – roughly the size of a mid-level brand at a large packaged goods or apparel company. For a point of reference, if there were even 100 DTC companies with $500 million in revenue (and there almost certainly are not) those companies would collectively generate only $50 billion, a figure which would be exceeded by three individual CPG companies. While certainly successful as start-ups go, few of them can be considered to be world-beating at this point in time.

- Recent revenue growth trends are arguably more a function of industry, product exposure and low market penetration levels rather than because these are DTC businesses, per se. For example, pet ownership, food delivery and at-home exercise all grew rapidly through the pandemic, and companies focused on those opportunities are growing quickly. By contrast, the need for personal care, bedding, eyewear and footwear was strong but much less robust over the past year.

- Although there is only a limited history to point to at each company’s current scale, most of the group is not cash flow positive. This point is important because arguably most incumbent companies in these sectors with brands generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue would probably be cashflow positive. Of course, investment in future growth is important, and losing money in support of that growth can be positive, but it’s far from certain that DTC business models can ever achieve the kind of profit or cash-generating levels that incumbents in the sector are used to seeing.

It’s important to keep in mind that many DTC businesses will surely prove their durability and become substantially larger in the future than they are today. Even at a small scale, their high intensity of advertising as a percentage of revenue is important because they remain outsized contributors to the growth of media, especially including digital platforms. However, the bigger impact of the emergence of the DTC concept relates to the new approaches they have pioneered as they provide incumbents in related sectors with new business models to consider for their legacy brands or those in which they will invest in the future. Given the scale advantages incumbents possess in manufacturing and distribution, they may be able to manage such businesses more profitably too.

Packaged Goods Companies Are Growing Rapidly Vs. Pre-Pandemic Levels (Despite Limited Role For DTC Brands In Their Portfolios At Present)

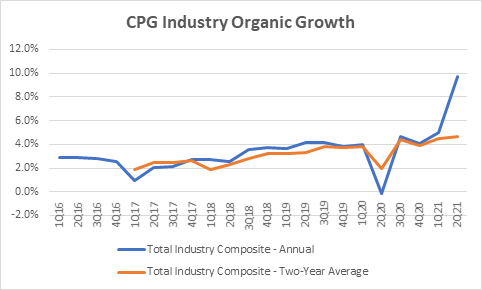

Incidentally, whatever fears the traditional packaged goods companies might have had about DTC businesses have surely abated, based on what we saw during the most recent quarter. Over that time, the global CPG industry grew 8.9% in 2Q21 led by a massive rebound in beverage sales and still grew 4.6% on a two-year compounded basis on broader strength, which allowed the category to perform well above pre-2019 levels of under 4%. Overall, the pandemic caused a wide range of changes in consumption and spending patterns, and so too has the recovery. But above all, the packaged goods industry appears to be in very rude health, despite many ongoing challenges.

Source: GroupM analysis of company reports

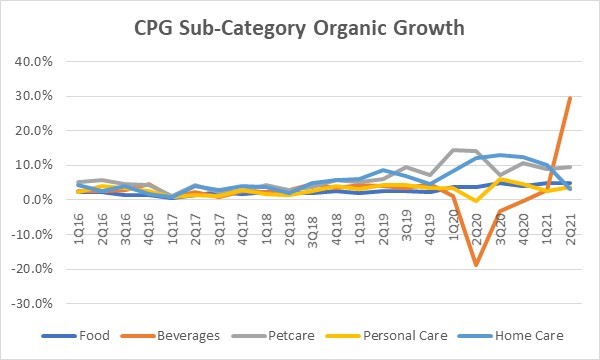

Looking at sub-composites of different categories of CPG, Food was relatively stable and grew by 4.9% annually, similar to levels observed throughout the pandemic, as presumably, consumers have eaten at home more often than may have been true in prior times, and when growth for the group was typically closer to 2%. Non-Alcoholic Beverages expanded by a headline-grabbing 29.6% in the quarter, although following last year’s 18.9% second-quarter decline, the average growth rate over this period amounted to 2.5% – exactly where it was in 2017 and 2018. As alluded to above, Petcare units tracked here, are sustaining pandemic-era trends, with the category up 9.6% organically, building on last year’s 14.1% rate of expansion. Personal Care appears to be “back to normal”, growing 3.8% in the quarter despite the easy comparable with a slight decline. In most years over the past five, this category has grown on an annual basis in a range of 1-3%, so this quarter’s two-year average would fall within that range. Meanwhile, Home Care is exhibiting somewhat volatile trends within the category: across the five companies with business units squarely in the field, we can calculate 1.4% organic growth in the most recent quarter, building on last year’s 12.9% base.

Source: GroupM analysis of company reports

Changes in China’s Technology Industry, Changes For Global Marketers To Adapt To

In what is probably one of the biggest trends for the global media industry this year, in recent months the Chinese government has taken significant actions impacting their domestic technology industry, with several new items emerging in the past few weeks alone. Directly affected companies include many of the world’s largest sellers of advertising, with capital raising, antitrust law enforcement, data privacy and corporate governance activities all representing affected areas.

Beginning with the cancelled Ant IPO in November last year and continuing with the fallout from Didi’s public offering in June of this year, last month came a report from Reuters stating that Chinese regulators are considering requiring companies seeking US listings to “hand over management and supervision” of their data to state-backed third-party firms” the government. These actions combined with the sudden ban in July on for-profit education companies effectively limited access to foreign capital, which primarily impacts tech companies. Fines levied or threatened for violations of antitrust laws, such as the nearly $3 billion fine applied to Alibaba in April, represented another front for the government’s more active role in the sector. And then in August, the government also passed a new data privacy law set to come into effect in November. Under this backdrop, there have been many senior executive changes at companies operating across the sector as well, as we saw at Bytedance and Pinduoduo earlier this year and at JD.com just this past week.

With similarly wide-ranging implications, media content has now come into focus, with a flurry of announcements made as the summer wound down. First, on August 25, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced a series of measures for the online world related to celebrities, including the banning of celebrity rankings based on popularity or other consumer-driven assessments, increased scrutiny of fan clubs, restrictions on inducements to consume celebrity-related products and prohibitions on the sharing of gossip. Second, on August 30, the National Press and Publication Administration announced restrictions on video game usage by individuals younger than 18 to fewer than three hours per week. And finally, on September 2, the National Radio and Television Administration announced its own series of measures for the Chinese television industry which included prohibitions on celebrity-driving elements of the medium – such as “Idol”-like programs – and restrictions on the use of talent who “have lost morality in their words and deeds.” Perhaps most notably, the new rules also prohibit “girly” aesthetics for men who appear on television.

All of these changes are attention-worthy for global marketers operating in China as they neutralize content many consumers might otherwise have been heavily engaged with. Consequently, strategies that marketers might apply elsewhere around the world may diminish in relevance within China and may require some global brands to take divergent approaches in different markets.

For example, some categories rely heavily on celebrities in their marketing. Brands operating in China will be less able to do this and may instead choose to focus more on product features or pure performance-based strategies. Similarly, brands that focus on exclusivity in some parts of the world may need to focus on more egalitarian elements of their products in China.

More generally, as more restrictions are applied to content production activities, brands will also need to be increasingly mindful of divergences between cultural preferences expressed in media that is widely distributed and the attitudes that consumers convey in their day-to-day activities. The ways in which brands “borrow” brand equity from professionally produced content in most of the world may become less relevant in China over time if this occurs.

Finally, while video-game ad inventory targeting under-18s is not by itself particularly meaningful for global marketers, gaming-related ads targeting over-18s are increasingly important. To the extent that reduced video game consumption negatively impacts the development of the gaming industry in China or causes a reduction in consumption as younger audiences age, the relative importance of gaming as an advertising environment may be lower in China vs. the rest of the world.